In this essay, I would like to unfold the meaning of Doris Salcedo’s quote. To do so, I would like to introduce her work and some of her other opinions about the art world. Secondly, I would like to focus on the fact that artists can be influenced by what they have learned, by culture, by money they want to gain or by other aspects, to do their job. Furthermore, I would like to expand the ‘uncanny’ subject and the artist’s unconscious in order to understand if the artist’s mind could be free of any kinds of archetypes that might limit his/her work. As a tool for explaining this, I would like to choose Guest at Grey’s artist Jack Webb and his performances.

To understand the meaning of the quote ‘The oft-celebrated freedom of the wrist is a myth’ by Doris Salcedo, it is necessary to raise a few questions. First of all would be — who is Doris Salcedo? Secondly – what does she means by the often-celebrated freedom of the artist? And finally what is the context of this statement?

Who is Doris Salcedo? Doris Salcedo is a sculptor who graduated from Fine Arts at Universidad de Bogotá, Jorge Tadeo Lozano in 1980 and then completed her Master of Fine Arts at New York University. Her work has political background, with a focus on the civil war in her homeland, Colombia. To comprehend her opinions about art, it is crucial to understand her origins and the way she makes her artworks. Salcedo grew up in Colombia, in the ‘third world country’ as she often says.

In the interview about her roots for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art she states:

“As an artist that comes from a third world country, you have very little access to see original works of art. So you do everything through books. And that makes a huge difference because we don’t have great museums with great collections. So you have a more of a theoretical approach to works of art. Also related to that I would like to say that, see as I come from the ‘third world’, we have this inferiority complex that I find as a privilege. Because we don’t have a mainstream culture, we have no previous masters in our art history, so it really gives a freedom in that sense. And it also forces us to reach out, to look towards Europe and the States, all the countries.”

But if so, she is putting herself in juxtaposition by saying in an interview with Charles Merewether in the book Art in Theory, 1900-2000:

“The civil war in Colombia defines a reality that imposes itself on my work at every level of its production. The precariousness of the materials that I use is already given in the testimonies of the victims. As a result, as an artist, I don’t have the opportunity to choose the themes that inform a piece. The oft-celebrated freedom of the artist is a myth.”

Though these two statements might not be in total opposite, why they seem to be in juxtaposition? In the first one, she admires the artist’s creativity and its existence even without deeper experience of art history. Salcedo is referring to ‘a freedom created by not having a mainstream culture, nor previous art masters in Colombia’, which she denies in the second statement by saying ‘[…] as an artist, I don’t have the opportunity to choose the themes […] freedom of the artist is a myth’. Rephrased it would mean that the fact that she was free of any role models did not give her any other chance than be inspired by the civil war and its victims. That opinion is for someone with an open and creative spirit, as the artist should have, very close-minded.

Nevertheless, there might be a bit of truth hidden in her various opinions. Artists might loose some of their freedom by the level of their education or their place of origin.

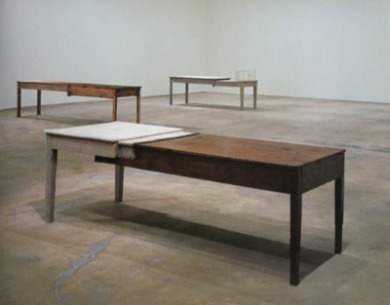

– Doris Salcedo – Unland

But the limitations of the artists’ freedom are not only in the knowledge and their nationality. Artists might be limited by their desire to become celebrated and adored by many. But what these artists might not realise is that if they become celebrated, they become mainstream artists. And if they once attract attention, it is hard to leave. So they might become focused too much on impressing their audience that the artists might forget who they were and what their work was about at the beginning.

A good statement on this can be found in John Carey’s book What Good are the Arts? on the page 27 by artist Sebastian Horsey:

“The artists play the well-remunerated role of court dwarfs… Why have they let it happen to them? Saatchi, Jopling, Turner prizes — these prizes are for turn-coats, cardboard outlaws who go on bended knee for an award from a society they profess to despise. What has happened to defiance? Why have the punk generation become so tamed, so emasculated, shaking hands with the royalty of the art-world and moving in circles that their work is supposed to scorn?”

This statement is a reaction on Momart warehouse fire in May 2004 in which were burned two celebrated artworks – Tracey Emin’s tent called Everyone I Have Ever Slept With and the Chapman brother’s Hell. This incident sparkled a wave of debates about money, talentlessness and corruption of contemporary Brit-Art. This might bring the question of the value of art – not necessarily in money worth, but what the artwork means for an artist. And is artist’s freedom restricted if he clings too much on his previous works and tends to continue work only within his chosen theme? Is the artist choosing the theme of his work? Or is the theme choosing the artist as Doris Salcedo said?

– Tracey Emin – Everyone I Have Ever Slept With

– Chapman brother’s – Hell

To continue with countdown of what else might limit the freedom of an artist, according to performer Jack Webb, ‘artist might be tied up by the moral rules’.

Jack Webb’s performances are focused on transformation, reprogramming and primal way of behaving. He is certain that: ‘we have no chance but transform.’ In his lecture given at Guest at Gray’s, he explained his ideas deeper. In his opinion, only the artist — in contrast to other people — is the one who can break these rules and might not be judged as a freak or a deviant. And therefore the artist should challenge these social tabus and do things that he fears to do in public to dare these rules and audiences that believe in them. And why should an artist do that? Because it is the only way to find out if these moral rules are still applicable and also how an audience perceives artists these days.

– picture of Jack Webb’s performance – GlitterGrid

Link for the video of Jack Webb’s performance: https://vimeo.com/41219373

Jack Webb’s performances, focused on the primal way of behaving and its criticism by the audience, make a connection with the lecture about Uncanny. Within that lecture were discussed two definitions of the word ‘uncanny’. First one is by Sigmund Freud from his book ‘The “Uncanny”‘ (1919): ‘that class of the frightening that leads back to what is known of old and long familiar’. The second one is by Schelling: ‘everything is unheimlich ( =uncanny) that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light.’ Within this lecture was also discussed that uncanny can mean something we desired in childhood but now it might frighten or embarrass us.

From these definitions can be derived that if something is brought suddenly from our unconscious to consciousness might cause discomfort to us. It is a reminder of our long forgotten or more likely repressed memory, desire or need, now slighted and morally unacceptable. That might be the answer on why Jack Webb’s performances make us restless. His movements are so familiar, though very distant and uneasy to watch.

The theme of unconscious is appearing throughout all the previous topics as a thin silver lining. From Doris Salcedo’s ‘opportunity to choose the themes’ through artists’ desire to be celebrated to the theme of uncanny and its origin.

The unconscious is a big part of human nature. It is known that the human brain is actively reinforced by both the conscious, but also the unconscious even if we are not fully aware of its influence. Our senses are receiving the full image of the world, but it is our brain that chooses what is important to put in our conscious. Other information is taken to our unconscious but they can still influence our actions. So we are not fully aware of what affects us. Therefore we cannot say where is the artist’s influence and if he/she chose the theme/material/etc consciously or unconsciously.

But at the end it was artists’ free will that decided to become artists in the first place. So celebrated or hated artists have made their own conscious decision to be artists and therefore the art they produce is nevertheless free, because of this decision. Even if Doris Salcedo was right and the freedom of an artist is a myth, how can we be sure that this myth ever happened?

References:

Lecture Memory

Lecture Uncanny

Guest at Grays with Jack Webb

Charles Harrison & Paul Wood (eds.) (2003) Art in Theory, 1900-2000, Oxford: Blackwell

Taylor B. (ed.) (2006) Sculpture and Psychoanalysis, Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company

Carey J. (2005) What Good Are the Arts?, London: Faber and Faber Limited

Eco U. (1989) The Open Work, U.K.: Hutchinson Radius

Defining Contemporary Art – 25 years in 200 pivotal artworks (2011) London: Phadion Press Limited

Interview with Doris Salcedo on her roots in Colombia for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, (2010)

Interview with Doris Salcedo on memory